- Home

- Explore >

- Notes from the trail >

- Hiking

- > Caro Ryan: Navigation for Beginners

It doesn’t feel like that long ago, that I used to marvel when I saw experienced bushwalkers or trampers look at their map, swivel their compass around and then stride off into the bush, with the kind of confidence one walks city streets.

It looked like a kind of mystical alchemy - tapping into some form of ancient wisdom - with no batteries required. At the time, I convinced myself that learning how to use a compass and read a topographic (‘topo’) map was out of reach. Without realising it, I had resigned myself to being a follower, behind someone else or relying on digital devices and apps to walk tracks laid down by other people.

I didn’t realise that using a map and compass is about so much more than technical skills using external resources.

Learning to navigate can unlock a new and deeper way of seeing wild places and experiencing the landscape and the wildness of everything around us.

Since marvelling at those compass users, I’ve fallen in love with maps, navigation and a new way of seeing myself in the natural world. I wrote the book, ‘How to Navigate’ and run courses to help share these skills with others. Needless to say, my perspective has changed on using a compass, so here are my top tips for anyone wanting to get started:

1 - Go gently - navigation can be learnt

It can be easy to feel overwhelmed when trying to learn a new skill. Especially if there is an existing mindset that says, ‘this is going to be hard/ too technical or out of my reach’ or ‘I’ve got a terrible sense of direction and always get lost’. Be encouraged - I can assure you that the skills of navigation can be learnt. Sometimes, I think certain people want you to believe it is a dark art or difficult to make themselves feel smart, but nah… you can do this!

2 - Find your NavHead

Speaking of mindset, there is a term I call putting on your NavHead. It’s about switching on your awareness and using all 5 senses to interpret the landscape around you. This type of mindfulness is tricky to switch on if you’re moving quickly, chatting with friends, or distracted by following a cheeky lyrebird/kea along a track. When you’re good at navigating, after lots of practice, sure, you’ll be able to multitask and do everything at once - then it will come naturally.

A great metaphor is learning to drive a manual car: at first, it’s a juggling act trying to time the clutch, gears, speed, turning and woah… traffic! But after driving for a few years, you don’t even think twice about jumping behind the wheel… or compass!

3 - The secret to never being lost is to always know where you are

I’m sure I can hear Yoda saying that, smirking to himself beside a swamp on the planet Dagobah, but it is one of the fundamental principles and keys of navigating with a map and compass.

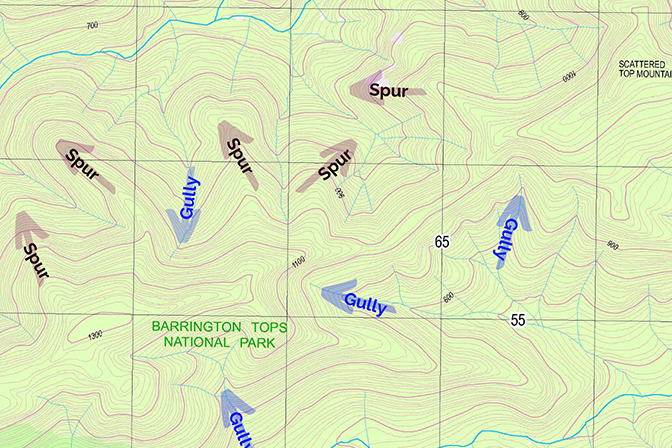

It cuts to the heart of a concept called thumbing the map and yep, it is what it says on the box: keeping your thumb firmly where you are on your map and as you move through the landscape, shifting it along as you pass the various features (man-made or natural). You could even think of it as ticking off landforms as you go, eg: ‘I’ve just crossed that creek - tick, there’s that spur coming down to me on the left - tick, and here comes the sharp right-hand bend in the river where it turns to the south.’

Think about it: when you arrive at a trailhead by a road, you know where you are. So if you put your thumb on the map at that point, put on your NavHead and move your thumb along the map as you go, you should still know where you are several hours on.

4 - Time

Speaking of hours, time and walking speed is a great way of calculating where you are on a map. Add in the extra factor of terrain (ascent/descent/surface) and you have the holy trinity of estimating how long a particular hike may take and where you are on the map. Thankfully, in 1892 there was a Scottish Mountaineer called William Neasmith who helped us out by creating a rule that helped us do the maths for folk of average fitness. 1 hour = 5 km of distance on flat, well-formed terrain. Plus 1 hr for every 600 m of ascent or 1000 m of descent. I also allow an extra 1 hr for every 5 hours of fatigue.

This is why one of the steps in putting on your NavHead at the start of a bushwalk, is to check the time you start. If you lose your place on the map or get distracted, you can calculate how far you’ve come along a track by the time. Eg. ‘I’ve been going for 30 mins on flat, easy ground, so I must be about 2.5 km from the trailhead.’

5 - Reading a topographic map

This could be controversial, but I think there is a LOT you can do with only a map, but only a FEW things you can do with just a compass. This is why I devote about 80% of theory time in my courses learning to read and understand topographic maps. I think of them like a storybook. By reading a map, you’re able to read the book before seeing a movie. The word topographic comes from the Greek, topos graphein: place + to write: The story of place.

You’ll know how steep, flat, long or tricky a trail is going to be, what you might see along the way and be able to plan a good spot for lunch, like a waterfall or lookout. Such a powerful skill to have!

And like Ikea flat pack furniture, a topographic map comes with instructions. Though many a DIY decorator may disagree with me, things become a LOT clearer when you read the instructions. My tip is to fight the urge to become overwhelmed by the masses of colours, lines, icons and symbols that you’ll find on a topo and instead look at the map key or legend.

Slow yourself down and read the whole thing, top to bottom, and you’ll find that the fine print, is very fine indeed. It teaches us a lot of things including the contour interval (ie. the vertical height between each contour line) and what the map scale is. For example, a 1:25,000 scale means that for every 1 mm you move your finger along the map, you are moving 25,000 mm (25 m) in real life.

6 - Reading ‘map to ground’

This is a term that describes standing in the landscape, (it helps if the map is turned around to match what you’re looking at - like when you used to turn a street directory around so it’s facing the same way you’re going - this is called orienting the map) and being able to see the different shapes and features of the world around you reflected on the map. ‘Oh, I can see a tall, stand-alone mountain on the horizon and there it is on the map… ah’. (cue: lights going on).

7 - Compass as a tool

There are a few different things that a compass can help you do and nearly all of them need to be done in conjunction with a topographic map - a compass by itself isn’t all that useful.

The one you’ll use the most is called Taking a bearing from a map. We use this when we know where we are (‘cos you’ve been thumbing the map like a boss) and want to know which direction to walk to get to our next destination. I use this about 90% of the time. There are others, like Taking a bearing from the ground or a back bearing, and depending on what you’re trying to do, are also good skills to learn.

Taking a navigation course, learning from an experienced friend and watching quality YouTube videos can help you learn the theory and techniques.

8 - Take a supportive friend and practice, practice, practice

Remember the learning to drive analogy? There’s a reason we can’t get our licence until we’ve put in some solid hours of driving practice with an experienced full-licenced driver. Grab the topo of your favourite or regular walking area and invite an experienced friend along. Choose your friends wisely, as you want someone who will let you learn at your own pace, not try and take over or cause confusion.

Slow down, it’s not a race.

Sitting at a lookout and pointing out the features, naming them and pointing to them on the map is a great exercise. Then, planning a route that allows you to walk with the land, not against it, working out times and distances (called a Route Plan or Route Card) and walking it while thumbing the map, ticking off the features as you pass them, is a great way to start your journey to navigation know-how.

Interpreting the squiggles and shapes of contour lines

9 - Questions to ask yourself

With your NavHead firmly on, here are some questions to ask yourself along the way:

- Do I know where I am?

- Where’s my next checkpoint?

- How far is it?

- How long will it take me to get there?

- What direction or compass bearing is it?

- What will I feel/see/experience on the way?

- How will I know when I’m there?

- How will I know if I’ve gone too far?

And most importantly…

Follow the 4 principles of the Think before you TREK campaign:

- Take everything you need

- Suitable hiking clothes, hat and footwear for the season and location

- Compass - you need a good base plate compass for navigating in the bush.

- Map case - to keep your valuable topo in top condition

- First aid kit

- Food, water

- + everything you’d normally take on a bushwalk or tramp

- Registered your intentions (tell someone exactly where you’re going… give them your route plan and let them know when you’re back)

- Take an Emergency communications device (PLB - Personal Locator Beacon or two-way satellite device),

- Know your route and stick to it